I had what I thought was a poetic notion: |

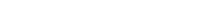

The DIG revolves around a mystery: The Israelis have discovered a 4000-year-old burial in a sarcophagus in Jaffa. What is it? How did it get there?

But the real story is about Sally Jenkins, a world-renown genetic archaeologist, who has been summoned to Israel. At the top of the field of ancient DNA, Sally has discovered a way to clean away eons of dirt and dust and replicate the material necessary to identify ancient burials, using infinitesimal fragments of bone. She's the only person in the world who can tell the Israelis what they've found. Flying to Israel the morning after her mother's death ("My mother can do this funeral without me."), she's met at the gate by her partners on the dig — an Arab-Muslim Israeli and a sabra, a former lieutenant general in the IDF. The drive from her hotel in Tel Aviv to their site in Jaffa begins the flood of recollections from her first time here, in this land, when she was seventeen, deeply in love, and braver than she has been since. Sally finds herself in a place where the mess of history — her own and that of the land she is working in — cannot be so easily cleaned away. From writer-performer Stacie Chaiken:

In 2003, the Center for Jewish Culture and Creativity commissioned me to write my next play in Israel. I spent nearly a year and a half mostly there — teaching, performing, and digging. I came home wondering what I might have to say about my experience in that luminescent land at that time, which happened to be during the Second Intifada. Things were blowing up. The central character in the dig is Sally Jenkins who is, like me, an American sent to Israel to dig. To come up with something. Sally is an archaeologist; her expertise is ancient DNA. I’m a writer-performer; I have a nose for story. We share a Hebrew names: Sarah. I came away awake to the palpable energy of the place, its blood-soaked history, and a sense that the conflict that defines the Middle East — between two peoples, Palestinian refugees and Jewish people, both of whom have been cruelly treated. Their identities have been created by the violence done unto them; violence they have done to others. |

|

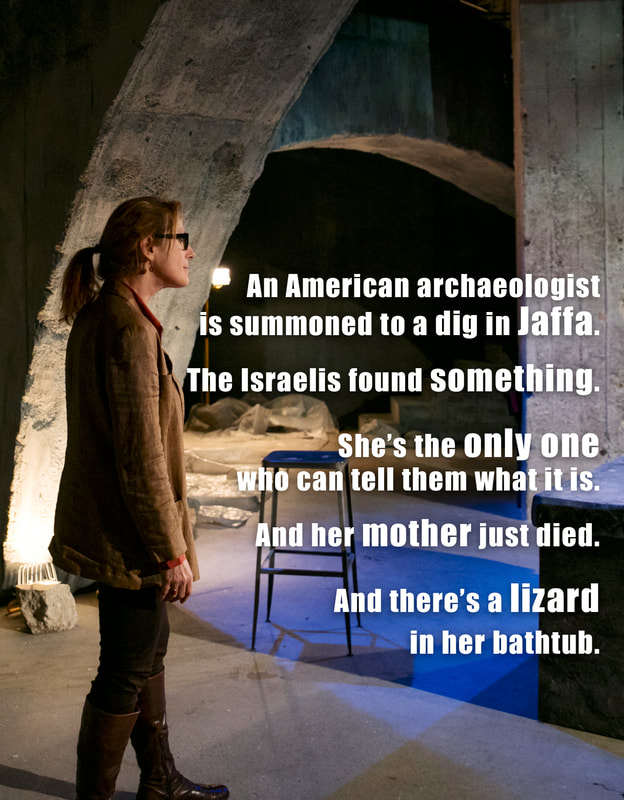

THE SCIENCE IN THE PLAY IS REAL

In 2005, when I started writing The DIG, the analysis of ancient DNA was cutting edge technology. Tom Gilbert, who was then in Copenhagen (now in the UK) spent hours with me on Skype, explaining how he had designed a technology that could clean away modern DNA and replicate the whole genetic chain from minuscule fragments of ancient bone. The study of ancient DNA is no longer all that new. The cutting edge genetic work is in the field of epigenetics, where researchers—in studies of Holocaust survivors and their children— have proved that trauma mutates genetic code, and that mutation gets passed down. Add to that the research of the 2015 Nobel laureates, who mapped the body’s ability to mechanically repair DNA on a cellular level. Their findings could lead to us being able to eliminate genetic predispositions to certain forms of cancer — and our ability to reverse mutation due to trauma. Might we be able to break that chain? |